In Conversation with Nora Krug

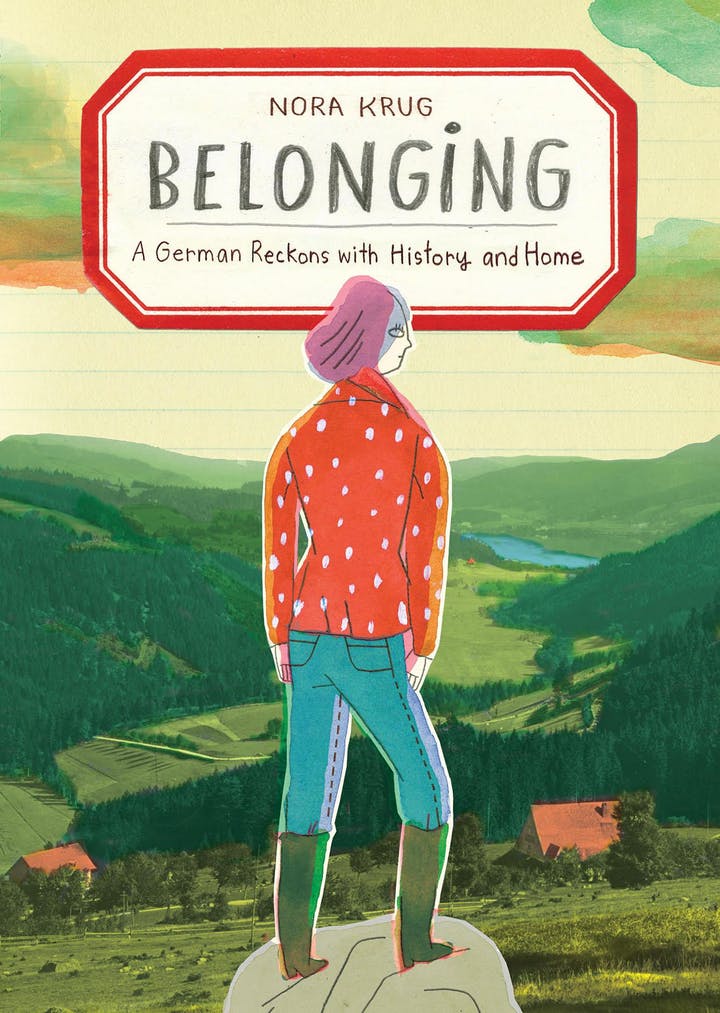

Nora Krug is a German-American author and illustrator whose drawings and visual narratives have appeared in publications including The New York Times, The Guardian, and Le Monde diplomatique. Her visual memoir Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home (foreign edition title Heimat), about WWII and her own German family history, was chosen as a New York Times Critics’ Top Books of 2018, as one of The Guardian’s 50 Biggest Books of Autumn 2018 and Best Books of 2018, and as one of Time Magazine’s 8 Must-Read Books you May Have Missed in 2018, just to name a few recommendations. Krug’s work has been exhibited internationally, and her animations were shown at the Sundance Film Festival. Krug is an associate professor in the Illustration Program at the Parsons School of Design in New York City and lives in Brooklyn with her family.

She was recently in Canada and So German had the chance to speak with her.

Does your decision to leave Germany at the age of 19 have anything to do with your feelings of guilt about Germany‘s past, with a certain uneasiness about being German?

I believe that many Germans of my generation have grown up with a strong feeling of cultural disorientation. And for some, this may also involve an attempt to find cultural affiliation elsewhere. I think that was the case with me, too. I moved to England when I was 19, studied there for three years, and then spent two more years in Germany. Then I moved to America. I think that was my attempt to identify culturally with another country.

For me, schools in Germany simply didn’t do enough to cultivate a devotion and love, or even a commitment to one’s own country. We grew up with this collective guilt, but not with a sense of individual guilt. At least in my experience, there was relatively little encouragement to do research into the history of one’s own family or one’s own hometown.

On a collective and institutionalized level, we actually addressed the subject of our guilt very thoroughly. But at the same time, we weren’t given the opportunity to say, “There is also our own individual horrible story that we have to continue to address.”

We also have to learn to love our country. That’s the problem with the political situation right now, that you can’t leave this confession of love to your own country to just the extreme right, because that‘s dangerous. But that is something that many Germans, including myself, still find very difficult: to look back with a critical eye but at the same time learn to celebrate and appreciate the cultural achievements of one’s country. Unfortunately, I am also one of those who still find it difficult to express this love.

Has your image of Germany changed as a result of writing the book?

I didn’t really free myself from the guilt because it was just too deeply ingrained in me… It was also never the aim of my book to free myself from guilt. That would have been too easy and also not appropriate. I think that as Germans, we should continue to deal with our history.

But through the book, I feel that I have made my contribution as far as the confrontation with the past is concerned. I think the book was an attempt to replace the word “guilt” with “responsibility”. So not to free myself from our guilty past but perhaps to think about how I can apply to my life what we have learned from our history, and what that history actually means to my own personal life.

I remember visiting a play in Berlin while I was researching my book, the play Brundibár, which was performed by children in the Terezín concentration camp. In Berlin, it was performed on stage by high school students. I wanted to see it because I wanted to know how the younger generation deals with the subject now.

After the play was over, I interviewed a few of the students. One student told me that her parents had emigrated from Egypt. There was no family connection at all to the war and the Holocaust. Nevertheless, as a German, she feels responsible for dealing with the topic. And that’s why she took part in the play. That was a revelatory moment for me. I feel similar here in America. I’ve been here for 17 years now and have been an American for about three of those years. I think when you make the decision to live in another country, you have to live with the history of that country. This means you also have the responsibility to position yourself politically and to defend that country’s democracy, no matter where you come from. The history of the country you live in becomes your own history. That is why I think it is so important that Germany should also teach courses in Holocaust history as part of its integration work for new refugees. Because I think it’s important that someone who chooses to live in Germany is just as well informed about the subject as those Germans who grew up there – because there are countries where the subject is completely swept under the carpet.

Was there a specific moment when you decided to write the book?

It wasn’t necessarily a particular moment, but a series of different moments. On the one hand, of course, the intensive political education at school and also the visits to concentration camp museums and so on, and then also many of my stays abroad. I spent time abroad early; I was also a student in Canada at the age of 16 for three months. While living in America, I realized that as a German, I am not only a representative of myself or my family but also of my country. As a German in a foreign country, you represent both yourself and your country, so you automatically always represent the history of your country – especially in a city like New York, where the German language is still strongly associated with painful memories.

Here I quote Hannah Arendt, who said: “When all are guilty, no one is”. I think if you live in Germany, among people whose families were followers, you don’t necessarily have the urge to ask further questions. Then you might come to the conclusion quite quickly that everything has already been said, that everyone was a follower. I think this is the wrong attitude because the group of followers is the group that needs to be looked at more closely, because this is exactly the group whose guilt is difficult to measure, the group that can shed light on how dictatorships come to be in the first place.

You have to be able to understand this grey middle mass in order to comprehend why Hitler was so successful. As a German living abroad, I was often confronted with my country’s history, and also with negative stereotypical ideas about Germany. For example, that the German language is very harsh, and that it is a cold country where it always rains. It’s quite strange how little understanding there actually is about what Germany looks like now and also of how much we have done to try to come to terms with the past. But of course, it’s also quite normal, because someone who didn’t grow up there can’t really know that.

A key moment for me was a chance encounter with a woman on a rooftop in New York sixteen years ago, a scene with which the book begins. This woman was in Auschwitz where she met Josef Mengele personally, and other people you only learn about in documentaries. At that moment it became clear to me that everything I learned at school was physically manifested in this woman who stood in front of me. At that moment I understood that history is also part of the present. That the two belong together, that we are made of history and therefore we must continue to acknowledge it.

I probably wouldn’t have written the book if I had stayed in Germany.

Can you tell us a little bit more about the creative process, about creating the book?

I am an illustrator. I studied various different visual disciplines, and at some point focused on illustration as a medium entirely and got a master’s degree in narrative illustration here in New York. For years I had drawn and written visual short stories about the lives of people who had experienced war, but who were neither war criminals nor ”heroes“, they were people who belonged to this grey mass. I wanted to learn about war from a perspective different than the one you’re exposed to in the media, for example.

I wrote a story about a surviving Japanese kamikaze pilot, and about an American soldier who fled to North Korea during the Korean War. And then at some point I realized that the reason why I always drew stories about the war was that I am German and that the subject of war had always been present in my mind – but that I had always avoided telling the story of war from a German perspective because I felt that I had no right to do so. And then I realized that I could no longer avoid the subject, and that it was so deeply ingrained in me, and that all my knowledge had been learned on a collective level. That I didn’t really know anything about my own family.

The writing component, not the drawing, was what was new to me. War and memory are very visual. For me, it’s also a very natural format for this project. When you think of historical books, you always think of books with text only. But in reality, our memories and our historical consciousness are strongly influenced by visual ideas.

Through the collage-like and diary-like character of the book, I wanted to depict the fragmentary nature of memory, the way we remember the war. I spent two years doing research, then two years writing, and another two years illustrating the book.

We read that you yourself translated the book into German. How did that unfold?

I chose the English language because it was easier for me to approach the subject from a distance. Originally, I also had an American audience in mind. When I was in the middle of illustrating it, the German publisher wanted to publish the book first, being afraid that Germans would otherwise buy the American edition because they all speak English. And that’s why I had to translate the book into German while I was still in the process of finishing the English edition.

What is next for you?

I’m in the process of talking to an American historian about working together on a book that will also talk about the coexistence of the past and the present. I need a break from my own books for a little while. That was a very exhausting and tedious project, and that’s why I want to work on a short-term project before I embark on my own, new book.

Thank you very much for this interview Ms. Krug.

At that moment I understood that history is also part of the present.